How do you make something like Jackbox?

In this post we are exploring games like Jackbox and other multiplayer games.

Building online games is never easy. There are a lot of moving parts with building one. How do players access and join the game? More importantly, how do people interact with the game? There are a lot of questions to answer with building an online game. You can go in any direction you want.

One of the online games I appreciate is Jackbox. Jackbox is a fun game you can play with friends and family that allows anyone with a phone to participate. The good thing about Jackbox is that you don’t need additional controllers (like you would in a console) or the system itself (like handheld systems or consoles). Only one person has a copy of the game, and they can start a game from their client for others to join via anything that can run a browser.

For me, Jackbox is an intriguing system. It is something that puts accessibility in front of everything else, which I like. This inspired me to try to build a similar system that allows a client to start a game, and allow others to join and play the game. I called my project Tarbox.

Well, how can you implement something like this?

The Parts

At my first glance at how the project architecture would look, these were the parts I came up with:

- A desktop client that has to be downloaded by a user.

- A server that accepts requests from the desktop client to start a game.

- A web interface that can allow other players to join the game.

- A database that would store the game information to do queries later in the future.

Great!

For simplicity, I have decided to implement the game service and the web service to be on the same server. I would separate the functionality with separate controllers, which would make the maintenance straightforward. In this approach, I would have a game controller and a web controller inside my main server.

For the main server implementation, I have picked Spring Boot since it was easy to start on and I have experience with Spring in general.

For the technologies used in the desktop client, I have picked Electron and React because of the reactive nature of the desktop client to my game. Just like in Jackbox, the desktop client would be the main driver in the experience of the players. There will be likely a lot of moving things and state changes that has to be presented in the screen, which makes React a good choice to use with Electron. By picking Electron, I also had the opportunity to get experience with one of the most popular ways to develop desktop applications today. I knew that Electron was a trend in desktop applications because of its portability (Slack, Spotify, VS Code, and many others are using this framework…). For the components library to use with React, I went forward with Chakra UI since I had some familiarity with it.

For the database, I went with good old Postgres.

Before implementing with Websockets

Before starting the project, I thought that I could achieve the implementation of the project without Websockets. At my initial implementation, I used SSE (Server Sent Events) to receive notifications from the web interface to the desktop client that the players have joined. For this to work, I had to use webhooks, where I would have a webhook URL that would be called whenever a player was joined. This led to a lot of overhead, mainly because I had to have a separate webhooks table in my database that would be connected to games via a foreign key. Although this allowed me to not use WebSockets at first which comes with its overhead, this was too much for this particular project. With the future of the project in mind where I had to use Websockets for the live update of the player joins as well. I had to switch the implementation with SSE back to Websockets.

For Websockets, I have used StompJS.

Into the world of Websockets

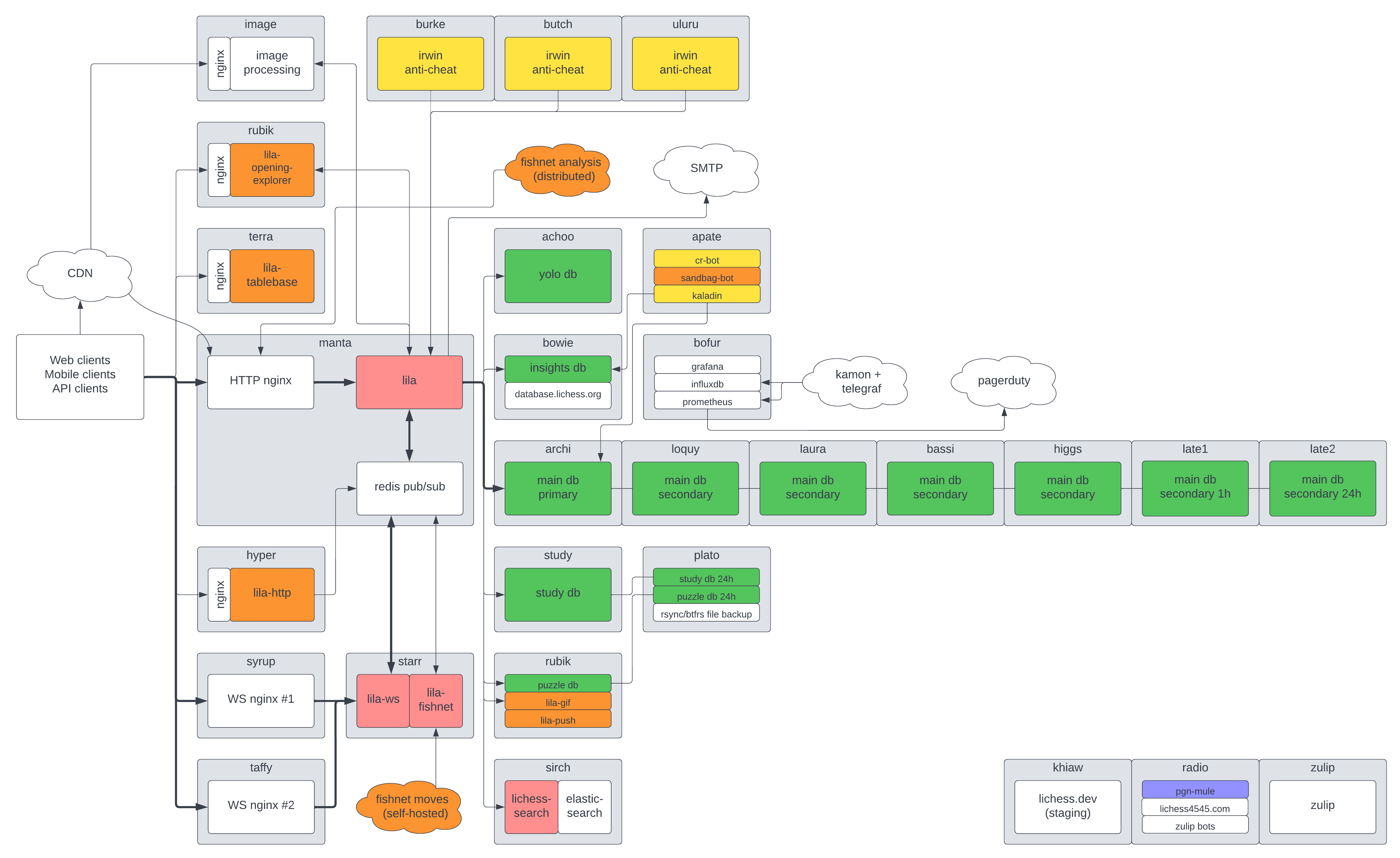

Turns out, StompJS is not that hard to implement with Spring Boot. What is interesting is that other projects that I took inspiration from, mainly lila which is the backend service of lichess.org, would have a separate Websockets server in their architecture. Here is the picture of the architecture that Lila relies on:

If you see the starr server which includes lila-ws, you will see that it is in a separate service from Lila which is the main monolith for lichess.

I was boggled by this at first, but then it became clearer to me. In a scenario with many games happening in parallel, most of the requests to my system would come to my WebSockets service, so it would make sense to separate it. In my case, since my goal for Tarbox was to be a learning experience, I have decided to keep the WebSockets within my Spring Boot server. This would make managing the application easier, but if I was building a real project with scale in mind, then I would consider separating the WebSocket server.

Decoupling the game from the view

Another big decision was coming up was the desktop client. I wanted almost all the game logic in my desktop client instead of the web server (which would kill the point of the desktop client in the first place). When I first implemented the Wordfinder game, all the UI code and the game code were mushed together. Most of the driving code of the code was coming from the UI, which made decoupling not trivial. In the end, I went with the callback pattern, where the callbacks are passed from the UI to the Wordfinder object which would contain all the logic of the game. This is what a snippet of this technical decision looks like:

// Callbacks

private onError : (message : string) => void = () => undefined;

private onPlayerAdd : ( player : string ) => void = () => undefined;

private onDone : (currentPlayer: string, stats: Map<string, PlayerStats>) => void = () => undefined;

private onAnswer : (body : any) => void = () => undefined;

private onEnd : (body : any) => void = () => undefined;

private onBeginNextRound : (picker: string, stats: Map<string, PlayerStats>) => void = () => undefined;

private onStart : (players: Map<string, PlayerStats>) => void = () => undefined;

private onDisconnect: () => void = () => undefined;

These callbacks are settable by the client, in this case, the game view which allows the decoupling the game from the view.

This made two things possible:

- Firstly the game was much more testable since I could mock the callbacks.

- Made the UI code much simpler to work with since I could just worry about how the UI would look like, knowing that all the game data was coming as an argument to the callback.

I engineered my code approach based on the fact that there will be more than one game in a real-world scenario, which is why I had to come up with a scalable way to write and test the games separately from the UI. Additionally, in the future, I could move the app to a separate frontend framework without too much hassle.

The web interface

The last piece of the puzzle I want to talk about is the web interface, aka what regular people would interact with in the game. One of my first principles in design was that the interface should be as light as possible since it is meant to be used by many devices that could have not ideal connectivity etc. Also, there is not much reactivity that is needed for the interface, since it is mostly forms or selectable things that you want basic input. Thus, I was OK using Web Components with vanilla JavaScript. The important thing is though I have still used a bundler with my javascript which helps with lightening the bundle size, which is already not much to start with since I didn’t pick a third-party frontend framework.

Deployment

For deployment, I have dockerized the Spring Boot server for easy portability. Since I have the one-year free-tier in AWS, I have moved forward with AWS. I have used an EC2 instance to deploy my Tarbox service, which is a Spring Boot docker image (I could have used ECS but I didn’t want the elastic capabilities for my case) and RDS for Postgres.

For my tarbox-games desktop application, I have used electron-builder to package the installers of the applications. I have used S3 to upload the desktop application binaries so I could pull them into my EC2 instance that runs the server. The reason I have used S3 to store the desktop distributions is because the binaries were too much for git to handle (I am not using git lfs), so I picked to choose S3 instead. With being able to pull the files from S3, I can present the desktop distributions as a downloadable asset.

Putting everything together

Putting all the elements together, I had a working online game with only the “Wordfinder” game, in which every player gets a turn to describe the word they are assigned to. Other players have to guess the word. In the future, I might implement more games if I feel like it.

You can check my tarbox-all repo. If you are on Mac, after downloading the game, make sure to do

xattr -d com.apple.quarantine /Applications/Tarbox\ Desktop.app

For future

If I wanted to pick up this project again, I would implement these things:

- Implement HTTPS

- Code Signing for the desktop app so the Mac users don’t have to do the

xattrcommand - Adding ‘recovery’ aka if a player accidentally disconnects the game without closing the browser they should be able to reconnect to the game in the current state.

- Implement more games!

Thank you for reading and hopefully you learned something!